BY VICTORIA GUDZENKO

Russia, one of the world’s largest natural gas exporters, has long wielded its energy resources as a tool of foreign policy. For the Kremlin, gas has not merely been a commodity but a strategic weapon to achieve political objectives. In recent years, however, this instrument has lost much of its effectiveness—signaling a shift in the geopolitical landscape and a gradual erosion of Russia’s international influence.

The History of the Gas Wars

Russia began actively using gas as a means of pressure after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when former Soviet republics and Eastern European countries started aligning with the European Union and NATO. Gazprom, the state-owned monopoly, emerged as a central player in this strategy.

As early as the 1990s, Russia demanded market prices for gas from post-Soviet states, while granting discounted rates to those showing political loyalty. Supply cuts were frequently justified by debts—often the result of Russia’s own pricing manipulations. In 1992, for instance, Russia reduced gas supplies to Lithuania in an attempt to keep it within its economic sphere of influence.

The company Gazprom was established in 1989 following the reorganization of the Soviet Union’s Ministry of the Gas Industry. After further restructuring in 1993, the Russian government partially privatized its shares—though more than 50% remained under state control. Today, Gazprom is the world’s largest gas company, controlling over 15% of global natural gas reserves and using this dominance as a political lever.

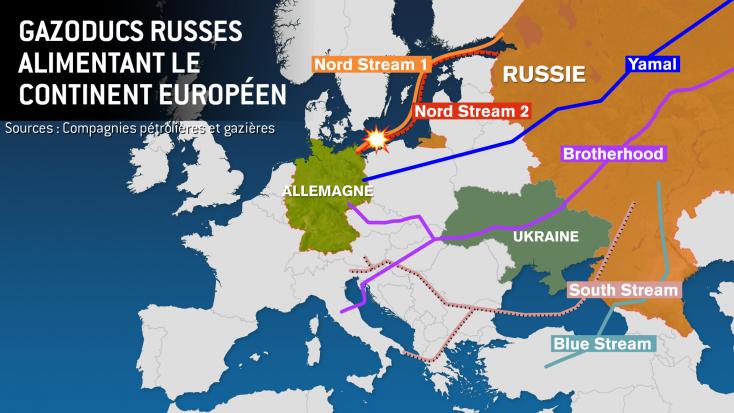

Russia intensified its gas wars in the 2000s following Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, turning energy resources into a central pillar of its foreign policy. It was during this period that the construction of new pipelines—such as Nord Stream—began, with the explicit goal of bypassing transit countries like Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland. The strategy aimed to tighten control over the post-Soviet space, exert pressure on European countries, and hinder the economic development of rivals through what became known as “gas tap diplomacy.”

Ukraine: A Key Transit Hub

In the decades following World War II, Russia actively developed its own gas fields, particularly in Western Siberia (Urengoy, Yamburg). By the mid-1970s, it had become the leading supplier of natural gas to both the USSR and Europe. However, due to limited domestic storage capacity, Russia relied heavily on Ukrainian storage facilities to manage supply and transit.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine took control of the Gas Transmission System (GTS) and the underground storage facilities located on its territory. Lacking adequate infrastructure for gas storage and transport within its own borders, Russia continued to depend on Ukraine’s system. While Ukraine provided storage services, Russia often failed to offer proper compensation, instead drawing gas from Ukrainian reserves without adequate reimbursement—fueling growing tensions between the two nations.

During the 1990s, Russia began rapidly expanding its own gas infrastructure to reduce its dependency on Ukraine. New storage facilities were built, and new pipelines were laid to bypass Ukrainian territory, including the Blue Stream pipeline to Turkey. By the late 1990s, Russia had fully integrated its new reservoirs in Western Siberia and was exporting gas through the Ukrainian GTS to Europe. Despite these developments, Ukraine’s transit network remained critical, as the new Russian pipelines were still insufficient to handle the full volume of exports.

Starting in the early 2000s, gas disputes between Russia and Ukraine escalated significantly. Moscow accused Kyiv of “stealing transit gas,” while Ukraine protested the lack of proper compensation for its transit services. Russia used these accusations to justify the construction of bypass pipelines such as Nord Stream and South Stream.

In the early stages of its gas infrastructure development, Russia was heavily dependent on Ukraine’s underground gas storage and transmission network. Only over time—after building its own infrastructure—was Russia able to reduce this reliance. Nevertheless, the past use of Ukrainian storage and pipelines was a critical step in establishing Russia’s gas export capacity.

The 2006 and 2009 Gas Wars

The first major instance of gas being used as a geopolitical weapon occurred in 2006, when Russia temporarily cut off gas supplies to Ukraine, accusing Kyiv of “unauthorized siphoning of natural gas.” At its core, the dispute was political: following the 2004 Orange Revolution, Ukraine had shifted toward integration with the EU and NATO—moves directly opposed to the Kremlin’s interests. The supply cut affected not only Ukraine, but also European countries dependent on Ukrainian transit routes. Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, and the Czech Republic saw a 30 to 40 percent drop in their gas deliveries. The conflict broke out in winter, when demand for gas was at its peak.

The 2009 gas war was even more severe. Once again, Russia halted gas deliveries to Ukraine for three weeks, citing disagreements over supply and transit terms to Europe. A new agreement was eventually reached, introducing a pricing formula based on European market rates. This conflict had major repercussions for Europe, which found itself without gas in the middle of winter. Bulgaria, entirely dependent on Russian gas transiting through Ukraine, suffered an energy collapse: factories shut down and heating was cut off. In Slovakia, the government declared a state of emergency, and some businesses had to scale back or cease production.

Hungary, which relies heavily on Russian gas, along with the Czech Republic and Austria, also faced supply shortages. Some parts of the Balkans were left without heating altogether. In response to the crisis, the EU stepped up its efforts to diversify gas sources and routes. The European Union invested in new infrastructure projects (Nord Stream, South Stream) and strategic gas storage. Russia’s reputation as a reliable energy supplier suffered a serious blow.

Russia’s Loss of Influence

Following the annexation of Crimea and the onset of the war in Donbas, Russia continued its gas blackmail—not only against Ukraine (which, since 2015, no longer buys Russian gas directly, instead using reverse flows from the EU), but also against Europe. Rising prices, discount policies for loyal countries, and the construction of new pipelines (such as Nord Stream 2) were part of a strategy aimed at deepening Europe’s energy dependence on Russia.

With regard to Ukraine, Russia had to change its methods of pressure. Gazprom tried to coerce Kyiv through international courts, demanding enforcement of the 2009 contracts. However, in 2018, the Stockholm arbitration ruled in Ukraine’s favor, ordering Gazprom to pay $2.9 billion to Naftogaz (Ukraine’s main energy company). This ruling dealt a significant blow to Russia’s blackmail strategy, which had included threats to completely halt transit through Ukraine after the contract expired in 2019. The launch of Nord Stream 2 was intended to deprive Ukraine of the $3 billion in annual transit revenues and to create an energy vacuum.

Belarus: An Ally Under Pressure

Russia has repeatedly restricted gas deliveries to pressure Belarus into making political concessions, particularly regarding integration into the “Union State” (a supranational entity created by Russia and Belarus under a 1999 treaty). In 2004, Gazprom cut gas supplies to Belarus to force it to accept market-based conditions, after years of benefiting from preferential rates. Then in 2007, following another crisis, Belarus sold 50% of Beltransgaz (the state-owned company responsible for gas transport) to Russia, and the gas price was partially increased.

In 2010, Belarus owed about $200 million to Gazprom due to non-compliance with new pricing agreements. In response, Gazprom reduced gas deliveries by 60%. Belarus then threatened to block the transit of Russian gas to Europe. By 2011, Belarus had completely lost control over Beltransgaz: in November, Gazprom purchased the remaining 50% for an additional $2.5 billion, becoming the full owner of the company, which was integrated into the structure of the Russian gas monopoly.

As part of the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), Russia promised Belarus to maintain preferential conditions on gas. However, disputes persisted. Minsk demanded price harmonization with those applied to Russian regions, but Moscow refused, arguing that the EEU did not involve unified tariffs. Belarus then accumulated a debt of $700 million by refusing to pay the price imposed by Russia. The conflict ended with a compromise: a reduction in the gas price in exchange for Belarus repaying the debt.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has consistently asserted that his country deserved preferential rates as a “sister nation” and ally of Russia. He used Belarus’s membership in the “Union State” to justify his claims, insisting that the Belarusian economy could not compete on equal terms with Russia without access to cheap energy resources.

After the 2020 protests in Belarus, Russia continued to exploit energy as a tool of pressure, supporting Lukashenko’s regime in exchange for further political concessions.

Georgia: Gas as a Tool of Punishment

After gaining independence in 1991, Georgia remained completely dependent on Russian gas supplied by Gazprom. This dependence allowed the Kremlin to exercise control over the country’s domestic and foreign policy. In the 1990s, Moscow artificially kept prices low, but starting in the 2000s, it sharply increased rates and used the energy debt as a means of pressure on the Georgian government. Moreover, most of the country’s gas infrastructure was under Russian control.

The situation changed after the Rose Revolution in 2003, which brought the pro-Western president Mikheil Saakashvili to power. Georgia then began pivoting toward European integration and sought alternative sources of gas. In January 2006, two explosions damaged a pipeline in Russia, interrupting gas supplies to Georgia in the middle of winter. Moscow officially attributed the incident to an “attack” carried out by unknown saboteurs, while Tbilisi saw it as a deliberate act of energy blackmail orchestrated by Russia.

At the same time, Russia raised gas prices for Georgia. In 2005, the country paid $63 for 1,000 m³. In 2006, the price increased to $110, then to $235—higher than the rates applied to many European countries. This crisis forced Georgia to accelerate the diversification of its energy sources. As early as 2007, it began importing gas from Azerbaijan via the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum pipeline. By 2009, Gazprom was completely excluded from the Georgian market. Today, Azerbaijan provides nearly 100% of Georgia’s gas, while Russia plays a marginal role.

Through this strategy, Georgia became the first post-Soviet country to completely free itself from dependence on Russian gas. After the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, the situation became even more complicated. Russia occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia, placing gas pipelines crossing these regions under its control. Faced with this threat, Georgia intensified its energy cooperation with Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Moscow attempted to use Gazprom to regain influence, but to no avail. In 2017, even Gazprom had to acknowledge its defeat in Georgia. Since then, the country no longer purchases Russian gas, except in emergencies and in very limited quantities. Its main supplier remains Azerbaijan, which covers more than 90% of its needs. Georgia now plays a key role as a transit country, enabling the transportation of gas to Turkey and Europe, thus strengthening its strategic position in the region.

Russia’s gas wars against Georgia peaked in 2006 when Moscow attempted to completely cut off the country’s supply to force political concessions. However, thanks to its cooperation with Azerbaijan and the West, Georgia managed to free itself from dependence on Russian gas and establish itself as a key energy player in the region.

Moldova’s Gas Dependency

After the collapse of the USSR, Moldova remained almost entirely dependent on Russian gas. Russia’s political influence hindered its attempts to diversify its energy sources. Furthermore, the absence of domestic energy resources and limited diversification capacities due to weak infrastructure put the country in direct dependence on Moscow. All gas deliveries passed through Gazprom and its Moldovan subsidiary, Moldovagaz.

The separatist region of Transnistria, in eastern Moldova, played a special role in this situation. Russia supplied gas there for free, creating a situation where Chișinău had to bear the financial cost, while Tiraspol (the capital of Transnistria) could develop its economy using these cheap resources. This region has not paid for its gas for over 30 years. By 2024, its gas debt exceeds 7 to 8 billion dollars (according to various estimates). Moscow demands that Chișinău repay this amount, although the gas is consumed by the Transnistrian Moldovan Republic (PMR), a non-recognized state. Moldova officially claims it is not responsible for this debt and refuses to acknowledge it.

This situation provides the Kremlin with a lever of pressure: it can manipulate the debt to blackmail Chișinău and demand political concessions. In the fall of 2021, the gas contract between Moldova and Gazprom expired. Moscow immediately seized this opportunity to exert blackmail, demanding political concessions: suspend European integration, recognize the Transnistrian debt as a Moldovan debt, and sign a long-term contract under unfavorable conditions. Faced with the urgency, Moldova had to accept a new agreement with Gazprom, but Russia deliberately reduced deliveries, forcing Chișinău to seek support from the European Union. The Moldovan government sought assistance from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), obtaining emergency funding to purchase gas from other suppliers.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the situation worsened further. Moscow drastically reduced supply, forcing Moldova to buy expensive gas from the EU. The Kremlin used this energy crisis to destabilize the government of Maia Sandu, while Transnistria continued to receive free gas, thus maintaining its industrial production.

It was only at the end of 2022 that Chișinău truly began to break with Russian dependence by purchasing gas via Romania and European markets. An alternative infrastructure was developed, allowing gas imports from the EU. The Moldovan government also intensified its investments in renewable energy and strengthened its cooperation with Brussels to modernize its energy system. In 2023, Moldova completely stopped buying Russian gas for the right bank of the Dniester (the area under Chișinău’s control). Transnistria, however, continues to receive gas from Gazprom, but this no longer impacts the energy security of the rest of the country.

For years, Moscow used gas as a tool of pressure on Moldova, threatening delivery interruptions and forcing it to bear the Transnistrian debt. However, after the invasion of Ukraine, Chișinău successfully reduced its energy dependence on Russia, diversified its sources, and moved closer to energy independence.

The Kremlin’s attempts to use gas as a means of political blackmail failed: Moldova received support from the EU and was able to diversify its supplies. A new example of the loss of effectiveness of the “energy weapon.”