As 2026 approaches, East Asia is once again emerging as one of the central theaters of global geopolitical reconfiguration. In fact, as early as the Obama administration, Washington had anticipated a shift in global tensions toward the South China Sea, viewing the gradual withdrawal from traditional conflict zones less as disengagement than as a strategic redeployment of U.S. power toward the Pacific—long perceived as the future epicenter of global geopolitics. The Sino-Japanese relationship, long characterized by a contained rivalry balancing economic interdependence with historical grievances, is now entering a more confrontational phase. The arrival in Tokyo of a new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi—clearly positioned on the right, openly advocating a hard-line strategic posture toward Beijing and explicit support for Taiwan—has accelerated this shift.

At the same time, Japan is methodically strengthening its strategic anchoring with the United States amid growing confrontation between Washington and Beijing. Remilitarization is no longer taboo, eighty years after the end of World War II. While this tightening of alliances may appear rational from a Japanese perspective, it carries major risks of regional polarization and unintended escalation. Are we witnessing Japan’s transformation into an explicit pivot of China containment in Asia, effectively delegated by the United States? And does this choice contribute to regional stability—or does it instead generate new systemic tensions?

Japan Facing China: A Strategic Anxiety That Has Become Existential

From Japan’s perspective, the hardening of its stance toward Beijing is first and foremost the result of a genuine strategic anxiety. The loss of its status as the world’s second-largest economy following the collapse of the financial bubble in the 1990s coincided with China’s unprecedented economic and strategic rise. China’s growing military capabilities, mounting pressure on Taiwan, accelerated militarization of the East and South China Seas, and increasingly assertive Chinese naval presence near Japanese islands have profoundly reshaped Tokyo’s security perception. China is no longer viewed merely as an economic competitor, but as a revisionist actor capable of challenging the regional order. In this context, the new prime minister’s recent and explicit support for Taiwan is not simply ideological—it is strategic. A Chinese takeover of the island would fundamentally alter the balance of power in East Asia and place Japan on the front line, militarily, commercially, and energetically.

As a result, strengthening ties with Washington appears to Tokyo as a strategic life insurance policy—one that also serves U.S. interests. Takaichi is fully aware of this. Since the end of World War II, the alliance with the United States has been the cornerstone of Japanese security. Faced with a China perceived as increasingly assertive, Japan’s instinctive response has been to anchor itself even more firmly to American power, even at the cost of increased strategic dependence. In this sense, the new prime minister’s hard-line stance is not a radical break, but the logical culmination of an evolution underway for more than a decade.

The Risk of Rigid Polarization and Strategic Entrapment

This strategy, however, comes with costs—and risks. By aligning ever more clearly with Washington, Japan contributes to structuring Asia around antagonistic blocs, at a time when the region had historically maintained a flexible balance combining rivalry, economic cooperation, and diplomatic ambiguity. China perceives Japan’s realignment as an explicit act of hostility. Each reinforcement of U.S.–Japan military cooperation, each declaration of support for Taiwan, each joint exercise in the region is interpreted in Beijing as another component of an encirclement strategy. This dynamic fuels a classic security dilemma: the more Japan strengthens itself, the more China feels threatened; the more China hardens its posture, the more Japan feels justified in doing the same.

In this process, Japan risks losing part of its regional mediation capacity—a role it had patiently built since the 1980s as a civilian power, investor, economic partner, and stabilizing actor. It also risks becoming a frontline actor in a Sino-American confrontation that largely exceeds its own control, potentially being drawn into crises whose timing and intensity it does not determine. Finally, this polarization threatens regional economic stability. China remains a major trading partner for Japan, starting with tourism—Chinese visitors account for roughly a quarter of all tourists to the country—and a lasting deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations would have direct consequences for Asian and global value chains.

Between Strategic Lucidity and the Trap of Alignment: What Choice for Tokyo?

The question, therefore, is not whether Japan is right to be concerned about China—it has ample reason to be—but how far it should go in strategic alignment and confrontation. This question is all the more relevant given that Washington itself, under Trump, has in recent months appeared to seek a more calibrated and transactional easing of tensions with Beijing. The challenge for Tokyo lies in maintaining a credible posture of firmness without sliding into a rigid bloc logic that would drastically reduce its diplomatic room for maneuver. This implies continuing to strengthen defense capabilities and the U.S. alliance while keeping political channels open with Beijing and avoiding the transformation of every dispute into an existential showdown.

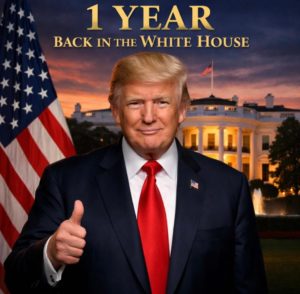

The Japanese prime minister’s upcoming visit to the White House, announced for March, fits squarely into this dynamic. It symbolizes both the solidity of the U.S.–Japan alliance and Tokyo’s deliberate strategic choice. But it will also be closely scrutinized by Beijing as a politically charged signal. As 2026 approaches, Japan stands at a crossroads, compounded by long-term economic challenges and demographic aging. It can become one of the pillars of regional stabilization—or one of the main points of crystallization in the Sino-American rivalry. Tokyo must avoid locking itself into exclusive alliances that would erode its strategic autonomy. Japan’s central challenge will be to remain a loyal ally without becoming a mere Western outpost, to support Taiwan without turning Asia into a new Cold War front.