By Alexander Seale (London)

The cool Dover wind sweeps across the almost deserted seafront. In the distance, the white cliffs stand out against a gray sky. Here, just 35 km from the French coast, the United Kingdom is watching the passage of migrants across the Channel. It’s a scene that has become the scene of an intense political battle. Nigel Farage, the hateful but rising figure of Reform UK, sees this as an opportunity for his shock plan: sending asylum seekers to Ascension Islands, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean—far from the European continent. As the British general election approaches, Farage has intensified the debate on immigration with his extremist proposals. He promises the construction of giant detention centers and guarantees mass deportations, claiming this will put an end to Channel crossings. Farage told The Times. “We have a massive crisis in Britain. This not only poses a threat to national security, but could also lead to public anger that is not far from disorder.”

Farage’s Shock Plan

Farage’s plan includes:

• Offering asylum seekers £2,500 to voluntarily return to their home countries, with additional plane tickets funded by the British government.

• Building detention centers to accommodate 24,000 people within 18 months of the election.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who came to power with a comfortable majority, has yet to show he can reduce the influx of asylum seekers, despite criticism of the previous government. The latest official figures show that 111,084 asylum applications were made in the UK up to June, including 43,600 by boat—a figure that has risen sharply since the pandemic. Over the past seven years, more than 157,000 migrants have attempted to cross the Channel illegally, with a new record of 6,600 arrivals in the first three months of 2025 alone.

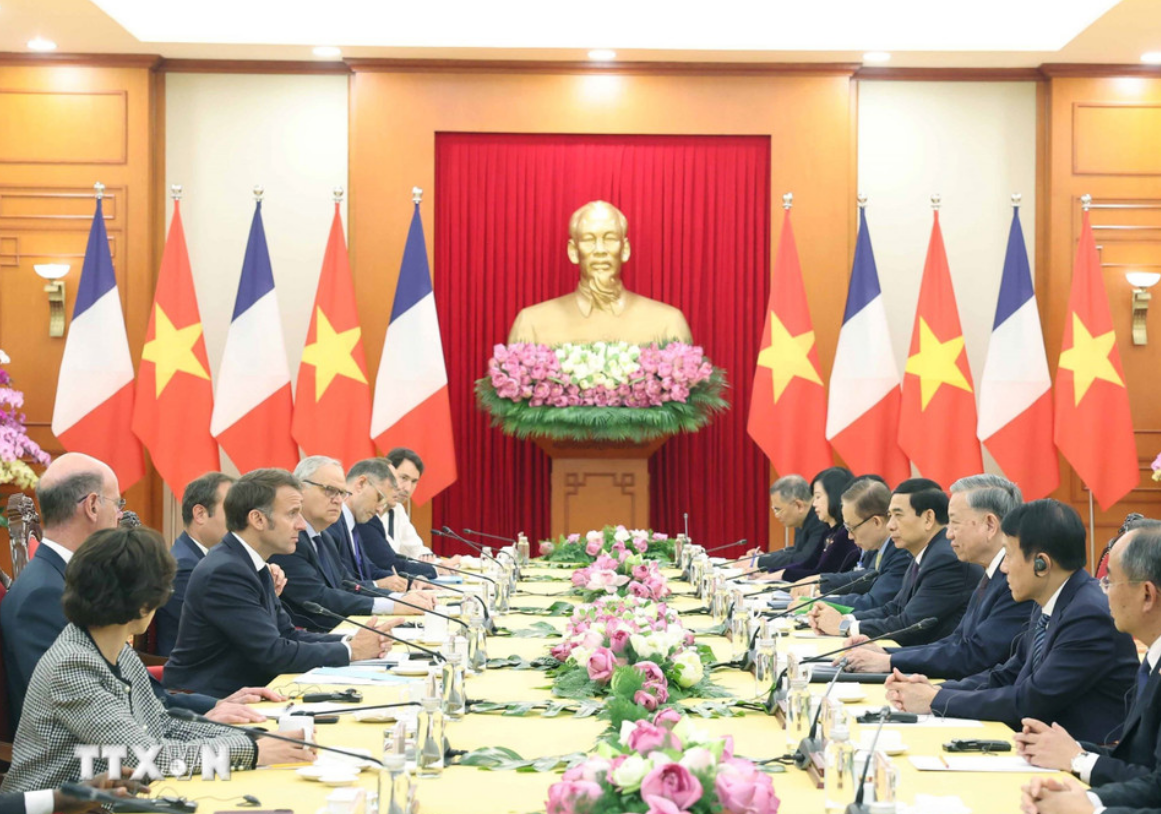

Agreement with France: Between Cooperation and Controversy

Starmer signed an agreement with France to return some migrants, but maintained the controversial policy of placing them in hotels and motels, which sparked local protests. “I am determined to break the smugglers’ business model and I am taking joint action with our allies to achieve this,” he declared. For Farage, the issue is also symbolic. The Ascension Islands, located about 1,500 km off the coast of Africa and 2,200 km from South America, is a remote British territory with military bases. Hot, dry, and with a limited water supply, it would represent an extreme refuge for reluctant migrants. “It’s far and expensive, but it’s symbolic,” Farage explained. According to him, his policy would cost £10 billion over five years, including £2.5 billion to build detention centers.

Keir Starmer and international cooperation

At the same time, Starmer called on the international community to unite to “eliminate people smuggling networks once and for all,” opening a summit bringing together some forty countries. Participants included France, Germany, the United States, as well as countries from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. The summit aims to combat organized crime, which is intrinsically linked to immigration; to share intelligence and tactics, and also to act “upstream” from the migrants’ countries of origin to the countries of arrival. International cooperation also includes discussions with China to limit the export of engines and parts for small boats used in the English Channel, and online advertising campaigns in Iraq and Vietnam to deter departures. These initiatives complement domestic measures, such as Starmer’s bill giving law enforcement powers comparable to those against terrorism, and tightening rules on nationality and illegal employment. People in Dover believe that the majority of asylum seekers are economic migrants, with a minority denouncing the presence of criminals. In Calais, Salem, a young Yemeni man, waits his turn for a meal offered by the Refugee Community Kitchen. Cigarette in hand, nervous, he recounts his journey through France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, fleeing the war in Yemen and hoping for a better life in the United Kingdom. “You don’t make friends here. You can’t trust anyone,” he murmurs. Most migrants intercepted by Border Force are never seen by British residents. They are taken to secure buildings before being relocated across the country. The majority (73%) are young men.

A decade of continuous growth:

Figures and facts

In 2015, the UK recorded 25,771 asylum applications per year.

In 2025, this figure had risen to 111,084 (including 43,600 arrivals by boat).

Despite the serious needs in the health sector—at least 31,000 nurses need to be filled —the border debate remains at the heart of politics.

Testimonies and tensions on the coast:

Nearly 200 migrants, mostly young men from Africa, queue for a meal. Among them, Tupac, originally from Gambia, recounts his journey to Europe and his aspirations for a new life in the United Kingdom. “I have a strong spirit and I can work, but they don’t give you opportunities,” he says of his country, showing poignant photos of his young children. On the coast, the cat-and-mouse game between authorities and migrants is constant. Three officers patrol every two kilometers, depending on the tides and weather. The maritime police intervene to prevent illegal crossings and access to the water. On August 11, former Conservative candidate Robert Jenrick posted images of what he described as “60 or 70 migrants in life jackets” near Dunkirk, highlighting the ongoing tensions over the migration issue. Between the Channel and the Ascension Islands, Farage seems to want to transform geography into a far-right political action plan, reminiscent of the colonial strategies of forced exile.