As preparations are underway in Geneva on July 5 and 6 for the first-ever Francophone Forum dedicated to the governance of digital technology and artificial intelligence, a central question deserves to be publicly addressed: Who owns the digital space, and in the name of what values is it governed? How will we be able to navigate this ocean of information in the future, constantly caught between virtuality and reality? How far will we be able to maintain our freedom? In just a few years, we have moved from a world where digital technology had become one of the guarantors of everyone’s freedom to evolve and flourish. Since then, concerns have been mounting, and as essayist Baptiste Detombe rightly asks in his book “The Dismantled Man: How Digital Is Consuming Our Existences?” » (ed. Artège), a central question persists: how can we continue to make all our screens a friend who wishes us well rather than a “digital ogre,” as he calls it, who would destroy us without us even realizing it?

Long considered a technical domain, reserved for engineers and technology enthusiasts, digital technology is now a fundamental issue of sovereignty. It structures our lives, our social interactions, our political decisions, and influences even our perception of reality. It is no longer a simple tool: it is a theater of geopolitical confrontations, where global power relations are being redrawn.

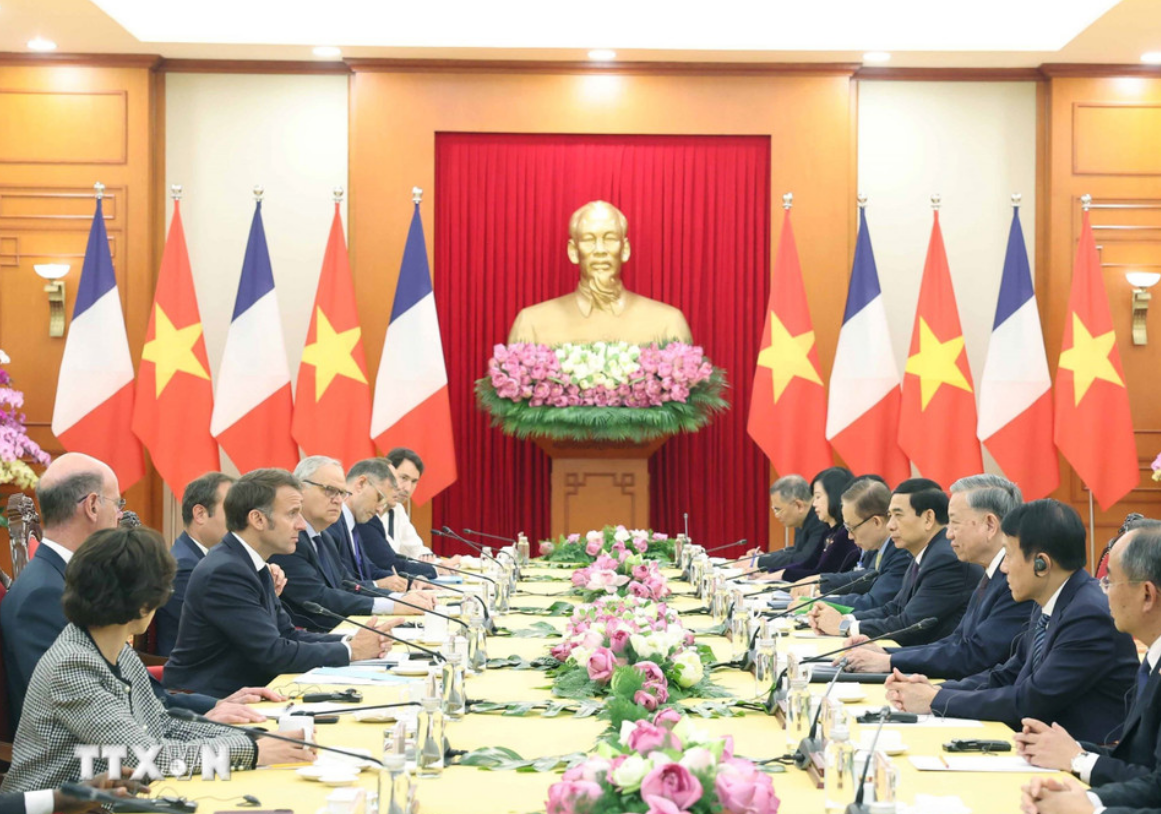

For twenty years, the digital ecosystem has been built outside of any restrictive multilateral framework. Over the past twenty years, ultra-powerful private actors—the American GAFAM, the Chinese BATX, but also new platform states like India and Russia—have taken control of a global virtual territory that no one truly regulates. They impose their technical standards, their economic models, their market or surveillance ideology, while massively collecting individual data for often opaque purposes. They are the ones who claim to offer total freedom to consumers. States, even among the most powerful, seem to be lagging behind, starting with those on the European continent. As for the countries of the Global South, they often have to be content to endure a digital architecture they neither conceived nor chose, but they manage with flying colors, thanks to young populations and promising public investment. The Global South does not want to miss its opportunity. The illusion of a free, open, and egalitarian internet has gradually dissipated. We are entering an era of fragmentation, polarization, and conflicts of interest. Behind every server, every algorithm, every social platform, lies a power struggle. The digital space, far from being neutral, has become a field of strategic, economic, cultural, and now political competition. This is why the Francophone initiative being spearheaded in Geneva takes on a special dimension. It affirms one ambition: to promote a plural, ethical, and inclusive digital world, countering the logic of unilateral domination. This requires defending digital sovereignty that is not inward-looking, but open to shared governance. It also involves making other voices and other values heard in the creation of technical, legal, and moral standards for the global digital world.

For what is at stake in the lines of code and data flows is the very shape of tomorrow’s world. Artificial intelligence deployed without safeguards or democratic deliberation can reproduce social biases, reinforce authoritarian control systems, or even legitimize the most coercive regimes. An internet dominated by a few cloud giants and a handful of monopolistic platforms becomes a colonized territory, where citizens are nothing more than passive and monitored users.

It is urgent to regain control. Digital sovereignty must no longer be a technocratic slogan reserved for international summits, but a global strategy of democratic resistance. It’s not about shutting down the internet or rejecting innovation. It’s about reopening the digital space to truly global, participatory, and equitable governance, where every state, every culture, every language, and every citizen can be an actor in their own digital destiny.

The Francophonie, through its diversity, its humanist values, and its potential for innovation, can and must play a leading role in this new battle of ideas. It’s time to break the strategic silence. Digital technology isn’t waiting.